“A bunch of young men all dressed in black dancing extremely aggressively on stage, it made me feel so intimidated and it’s just not what I expect to see on prime time TV”

– Skepta, Shutdown

Grime entered the most elite realms of British culture in 2018 when Wiley was invited to Buckingham Palace to collect his MBE for services to music. Unfortunately, the Daily Mail were too concerned marking the occasion with the headline “Grime Does Pay! MBE for drug-dealer turned rapper” focusing on Wiley’s past to deliberately reinforce negative stereotypes about black music and downplaying his actual achievements. This explicitly demonstrates how Grime music, amongst other urban dance music is targeted by moral panics in the media, and how such stereotypes have led to certain legislations to be implemented undoubtedly disadvantaging the scene.

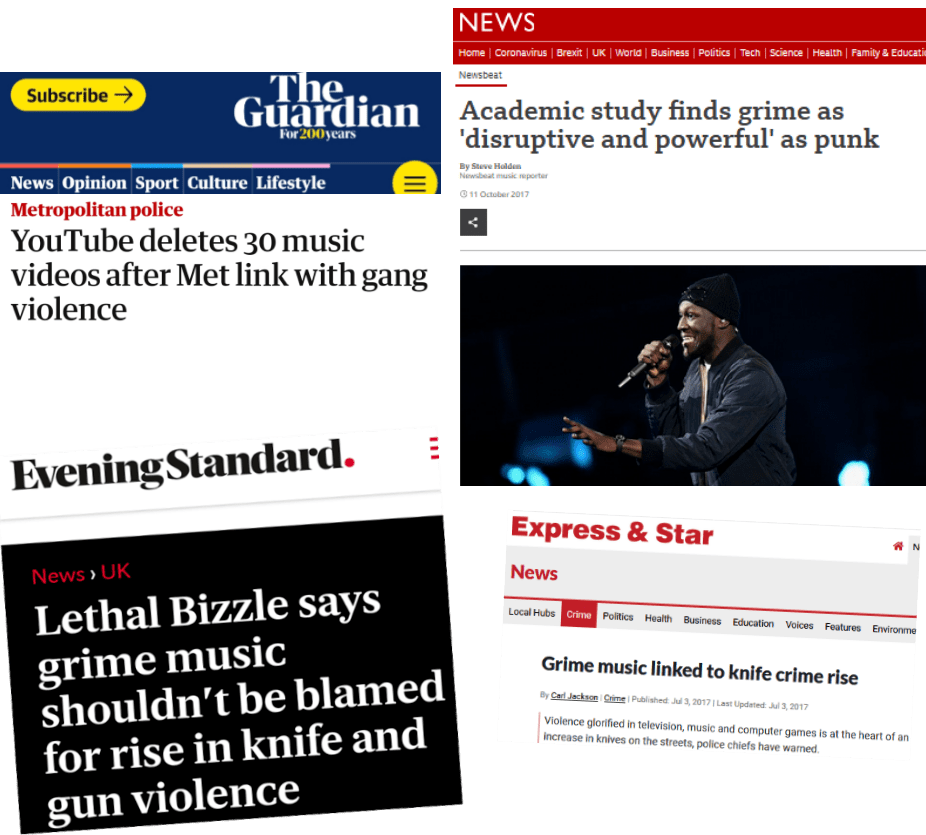

It’s at no surprise to anyone that due to the origins of Grime coming from the gritty council estates of London that the media regardless of factuality have something negative to say about it. Grimes intimate associations with the city implicate it within public discourse leading to mainstream media to adopt themes of drugs, gangs, knife crime and delinquency towards the scene. The discursive framing of the material accentuates a sort of ‘otherness’ towards Grime excluding both listeners and artists from certain fractions of the population, essentially creating ‘folk devils’. Cohen (2002) found that dominating cultures constructed certain youth cultures (like Grime) as folk devils that cause mass destruction and violence on a regular basis. Cohen (1987) believed folk devils were used as a sort of escapism for society, a scapegoat to distinguish which roles should be avoided and which should be emulated. For the Grime scene this is evident in media headlines:

BBC News | Evening Standard | Express & Star | The Guardian

So how does society as a whole receive information about this so called deviant behaviour? The body of information from which ideas are built is habitually received at second hand and arrives already processed by the media, meaning it has been subjectively altered depending on what constitutes as ‘news’. Sometimes the panic passes but most of the time it has more serious and long-lasting consequences on society such as changes in legal and social policy. The fear of mad, uncontrollable mobs is forever a recurring feeling in the mainstream press and in the discourse of governing authorities. The first law introduced in Britain around a particular music genre was in the 1990’s against dance gatherings in section 63 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act (1994) which was titled ‘powers in relation to raves’. The law provided police with the power to remove people attending or preparing a rave. While this applies to gatherings on land in open air, this example can still be applicable in terms of young youths raving to music with the ideas of moral panics and the placement of power in the police to discriminate certain groups. The 90’s music scene of acid house and free raves stemmed these discussions. Never before over years of post-war moral panic activities of teddy boys, mods, hippies and punks had the government considered young people’s music so dissident as to prohibit it.

This repetition, the idea that Grime music is exclusively linked to violence and criminality becomes unescapable leading to certain assumptions that have real effects in terms of restrictions on public performances. Most punitive was Form 696 introduced by the Metropolitan police in 2005 to ascertain whether particular live music events pose a particular risk of disorder. The ‘risk assessment’ form demanded the names, private addresses and phone numbers of all artists at live shows that featured either a DJ or MC rapping, as the rationale was that these shows would be of high-risk. The form would be used at events where trouble is expected, however it seems such preventive measurements serve to both reinforce the structures of inequality that Grime fights against, while at the same time limiting the ability to reach a larger audience. There is this underlying moral panic essentially about rap music but more importantly the race of black rappers and the type of audience that might be at these events. As Grime increased in popularity, promotors involved in organising live events expressed that the Metropolitan police were applying particular discriminatory measurements with the goals to ‘lock off’ venues and exclude certain artists from performing. In relation to Hip-Hop, So Solid Crew had a tour in 2001 and a festival appearance in 2002 cancelled after local police refused to work at the gigs, and ironically for Grime artist Giggs his London gig in 2010 was cancelled suffering the same fate. Form 696 is widely criticised for disproportionately targeting music of black origin, however the police on the contrary claim the risk assessment simply expresses what events may be known to be more risky than others. What seems quite perplexing is the way in which for the first time, the connection in the police’s perception between disorder and ‘black cultural events’ have been expressed and rendered visible on paper. The moral panics surrounding Grime and its lyrical content have rendered suffering for the scene with institutional racism implemented into police about certain music genres being linked to violence and criminality.

There is unquestionably a link between Grime’s ‘road’ culture of marginalised youths and with that characterised by spectacular aggressive, hyper masculine behaviours that incorporate petty crimes and violence. While the self-narratives of Grime artists highlight their struggles as a ‘means of getting by’ this does not mean its audience is going to carry out criminal activity, rather it is a coincidental link. Lyrics are discursive actions that help construct the interpretation of an environment where violence is acceptable, but overall rap music doesn’t cause such violence; violence is much more complex than that. Grimes whole concept is on generating ‘street capital’, thus these strong elements of braggadocio about crime and violence become part of Grimes vernacular which is entirely separate from the actualised ‘armshouse’ or violence of road. As DJ Bempah told the BBC “Music itself can’t determine what you go outside and do… it can glamorise it, but it can’t force your hand to commit those actions”. In response to form 696, ‘UK Music’ set up a campaign against it and by 2017 the form was scrapped after a fall in ‘serious incidents at music events’.

So why is there still moral panics surrounding Grime music, just because of its lyrical content? As discussed, this can only ever have illiberal consequences. Form 696 provides a clear example of how those hierarchies of power have tried to exclude and in some cases completely remove Grime from public spaces. It was highly suspected in the Grime community that the aim of the form was to stop the transfer of responsibility in which violence in London’s council estates was to blame by the social conditions of deprivation often described within the music. “They [police] target Grime a lot, they just blame a lot of things on Grime … we know they’re just trying to shut it down” says Grime artist P Money to NME. It seems questions still remain as to whether the media and police are accurately interpreting what is rhetorical gestures of street culture with that expressed in actual criminality.

Written by Nicole Horwood / Twitter: @Whorewoods