“Has Theresa May ever been to Aldi? Has she ever been to Lidl in her life? If she can tell me what Lidl looks like from the inside, I’ll listen to what Theresa May has to say“

–Saskilla live on BBC news after the election.

The Grime scene functions as a liminal space for the impoverished to express their anecdotal narratives of street corners, criminality and council estates evidencing stories of a generation on the margins of society. It’s partly about the struggles of being working class youths in London, but at the same time the stronger connotation is on those who are intersectionally Black and of working class origins. It’s through these stories that Grime artists display their identity politics.

It wasn’t until the 1950’s where music started to get political with the arrival of counter culture, anti-capitalist ideas and ‘the hippie move’ where lyrics placed people with particular intellectual ideas. By the 1980’s Hip-Hop music started to gain a position in Britain with the sounds of decaying urban life in black American resonating with the wasteland Thatcherism left behind in many working-class and ethnic communities. In the early 1990’s other new genres of music developed in the UK from drum and base, garage and jungle, with jungle particularly reflecting the dark post-Thatcherite “underclass” life created for black and white urban youths. This is where the inspiration and cultural roots of Grime came from, emerging in the early 2000’s. The dominating ethics of this genre possesses an inner philosophical doctrine and morality that is concerned with confronting power with truth, both through its art and as a culture with distinct identity politics embedded. Identity politics aims to reclaim greater self-determination and political emancipation for marginalised groups through understanding and challenging externally imposed characterisations, instead of organising solely around belief systems or party affiliations. Grime artists use their experience of being working class and the intersectionality of being Black and of working class to articulate political claims that help guide political action with the aim of gaining power and recognition in the context of perceived inequality.

Like many other black genres of music, Grime disrupts any antiquated notions of ethnic absolutism, and sits confidently within the Black Atlantic paradigm as a transnational and intercultural expression, however while Grime is sonically black it is at the same time ‘authentically British’. Gilroy (1993) argues that contemporary black music doesn’t seek to exclude problems of inequality, rather it facilitates a continuous commentary on the systematic and pervasive relations of domination that supply its conditions of existence. Black music is often a reflection of society, whether it’s the cultural reflexivity of Grime exhibited in for example, Lethal Bizzle’s ‘Police on my back’, the history of black experience is politicised within its lyrical content.

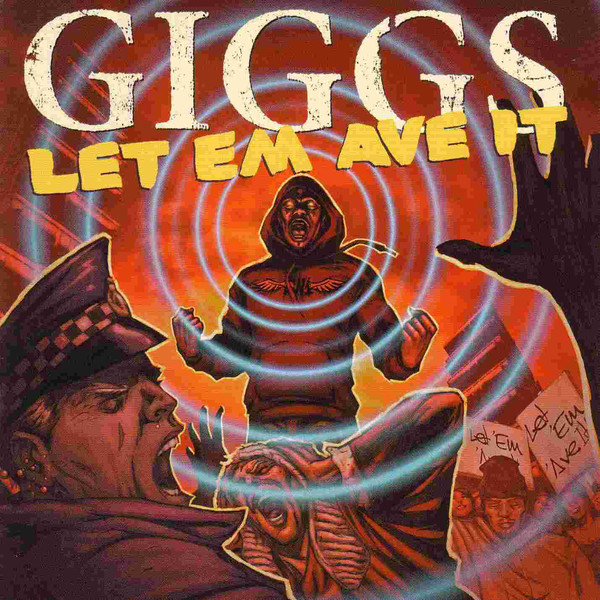

By highlighting this in music, Grime musicians are able to unify individuals around particular issues through its embedded ethics actively raising the political consciousness of young black people in this movement. Giggs’ second album ‘Let Em Av It’ is titled in response to police intervention into Grime music videos and how they were keen for these videos not to be filmed. The lyrics in ‘Sign’ highlight the struggles he faces in life and speaking his mind due to his blackness and working class roots:

So there’s no reason you should speak to me

I open up my heart let the people see

Told them they better start getting used to me

Wouldn’t be surprised if the police tried to shoot at me

While the lyrical content of Grime is not always explicitly political, the lived experiences of poverty and adversity is infused throughout providing artists with a unique real-life position in their communities as social commentators. You could argue Grime’s capacity as a form of testimony and an articulation of the young, black, urban critical voice has profound potential as a language of both liberation and social protest. Since the birth place of Grime came from the gritty council estates of London, the self-narratives set by artists incorporates such themes of socio-political relevance by highlighting their deprivation from the socio-economic and racialised margins. Grimes harsh and resistant lyrics are critical to understanding contemporary cultural politics where the complex process of people searching to create meaning about their everyday lives is subject to politicalisation and struggle. Grime is more than just music; it is a system of contentious innovation that rallies against the traditional hierarchies of power through its sound of disillusionment, resentment and despair.

A distinct example highlighting this is in Grime artist Dave’s track ‘Question Time’, ironically named after the BBC programme where audience members quiz politicians. The scathing seven-minute-long song demonstrations everything wrong with British politics, especially the governments mistreatment of the NHS:

All my life I know my mum’s been working

In and out of nursing, struggling, hurting

I just find it fucked that the government is struggling

To care for a person that cares for a person

So where’s the discussion on wages and budgets?

How they made them redundant when I was a young’un

These lyrics connect the social problems that we often consider ‘normal’ or out of our control towards the government’s maltreatment, especially to those from working class and ethnic backgrounds. Because of the rate of inflation and the fact that nurses haven’t had a pay rise, it means in real terms that they’ve had their pay cut in recent years, a trend set to continue. He levels criticism at the largely wealthy and upper class make-up of parliament, talking about how weird it is that the country is run by “people who can’t ever understand what it’s like to live life like you and me.” This perfectly paints a picture of emancipatory politics where modernity is concerned with liberation from the constraints that limit life chances. The attention is directed to the exploitative relations of class and the freeing of social life from the fixing of traditions such as ethics of justice and equality. Music can therefore be a powerful tool for political expression. This is why Wiley concurs that “it’s called ‘Grime’ for the same reason punk was dubbed ‘punk’; in order to draw attention to its scuzzy street origins”. Grime like punk, gave a voice to marginalised youths, it was “an opportunity to talk about what we knew, what was happening to us and around us” (Wiley, 2017).

The #Grime4Corbyn movement revealed just how important Grime’s embedded ethics were in actively raising the political awareness for youths in this movement. Lauren, chief operating officer at GRM Daily believes Corbyn’s success with Grime was his ‘realness’ and ‘truth’ that other politicians weren’t able to authentically express. It wasn’t just his anti-austerity and anti-war policies that won backing for Corbyn, but more so his approach to politics with a sort of do-it-yourself ethos similar to that of Grime’s culture. In place of the old top-down politics, Corbyn promised to offer a more positive, horizontal form of politics capable of harnessing grassroots activism. By engaging with the public and understanding the struggles of ordinary people, he was regarded as someone who “understood what it’s like to live life like you and me” (quoted from Dave’s song) because he offers a politics of humanity, respect and social justice, all of which chime with the identity politics of Grime artists.

Without the spatial imagination of Grime concerned centrally with the everyday lived experiences of people, the understanding of politics for youths would be inadequate in relation to real-life scenarios. The idea of identity politics facilitated throughout Grime lyrics helps youths from working class and ethnic backgrounds to position themselves not only in relation to the music but within politics themselves. They’re able to gain cultural capital and awareness of the world, simply by listening to their favourite artists.

Written by Nicole Horwood / Twitter: @Whorewoods